Let’s Enter a New Era of Options for Colorectal Cancer Screening

Colorectal cancer is the second-leading cause of cancer death in the United States. Rates are rising in younger – and middle-aged individuals. Multiple groups – such as people living in rural areas, certain racial and ethnic minority groups, and those with lower income – are at higher risk for colon cancer death. But a crucial FDA advisory committee meeting happening on May 23 may pave the way for a simpler screening option that could, through increased screening completion, catch the disease earlier for millions of Americans.

Screening can find colorectal cancer early when it is highly treatable, and even prevent cancers by pinpointing and removing the small polyp growths that turn into cancer, but too many people remain unscreened. Approximately 40% of eligible adults aged 45 years or older – a staggering 50 million people in the U.S. — are not being screened for colorectal cancer. Current options for screening include colonoscopy, a stool test that checks for blood, or a combination stool test that checks for abnormal DNA patterns and blood.

For nearly two decades as a researcher and gastroenterologist, I have worked to identify new ways to prevent and detect colorectal cancer, promoting screening options that can help people get checked. We have seen that doctors offering and explaining options for screening is one of the most powerful ways to help people get up to date. Doctors recommend colonoscopy and many patients choose this test because it has the highest sensitivity for cancer and polyps. Most doctors also recommend stool tests – and many doctors and health systems offer these by mail – with many patients choosing these tests because they can be conveniently done at home. But despite widespread availability of these options, we have not seen substantial gains in the rate of screening participation over the last 10 years.

The reasons are not surprising. Some people are not yet ready to do an invasive test, like colonoscopy, that requires bowel prep, a driver, and taking a day off work. Others are not ready to handle their stool because of the “ick” factor. Sometimes, people intend to get screened but get too busy with other life priorities once they leave a doctor’s office and don’t follow up. There is an urgent need for new approaches that can help people who are interested in screening but find current options unacceptable or inconvenient.

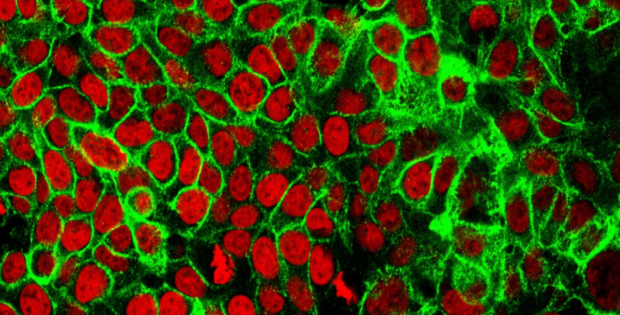

Innovations in our ability to measure markers of disease in the blood herald a new strategy: a blood-based screening test for colorectal cancer. In a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, a blood test that identifies DNA from colorectal cancers demonstrated 83% sensitivity for the detection of the disease, with 90% specificity for negative results. If added to existing options, a blood test that could be done at the time of a routine doctor visit could be a powerful tool to increase screening participation.

When the FDA advisory committee panel meets, they will be asked to vote on whether the test is safe, whether it is effective for colorectal cancer detection, and whether it should be approved as an option for colorectal cancer screening.

The most important discussions will not focus on whether the test is safe (because it is a blood test) or whether the test can detect colorectal cancer in people who have no symptoms (because it picks up about eight out of 10 cancers) or even whether it should be approved. More likely, discussion will center on whether the test will be approved as a screening test with or without a label limitation in which patients would be required to first decline currently established tests such as colonoscopy or a stool test, and then document the refusal prior to being allowed to do the blood test.

Arguments for a label limitation requiring refusal of other tests will focus on the theoretical concern that making a blood test available without this limitation could lead to marked substitution of existing tests with a blood test. Concerns about substitution are based on sensitivity differences between tests. While colonoscopy finds nearly all cancers and important polyps, the blood test picks up eight out of 10 cancers and one out of 10 important polyps. Stool tests pick up seven out of 10 to nearly all cancers, and two to five out of 10 important polyps. Also, while the blood test appears to have similar sensitivity for finding the earliest (stage 1) cancers as a stool blood test, this performance appears lower than for a colonoscopy or stool tests that look for abnormal DNA in stool. This concern is most relevant if a patient who is willing to do a colonoscopy instead opts for a blood test, lowering their chances of having a cancer or important polyp detected.

There is no available evidence to suggest that high rates of substitution will happen – on the contrary, there is ample evidence against this concern. Surveys consistently show that primary care doctors routinely recommend colonoscopy and options such as stool tests to their patients. This is likely why current patterns show that colonoscopy is by far the most completed screening test, and why offering stool tests has not led to substantial substitution effects that lower colonoscopy participation. Because doctors have a professional duty to discuss pros and cons of any healthcare decision, including cancer screening, we do not expect them to ignore sharing the tradeoffs of available tests, even with availability of a new blood-based option.

A label limitation requiring refusal of other tests based on concerns about substitution could do harm. It makes screening discussions more complicated and may lead to challenges such as requiring pre-authorization from insurance companies before a blood test is offered. Primary care doctors are under immense time pressures, and we want them to focus on discussing screening options, not paperwork. These issues could prevent people who would have been ready to complete screening with a blood draw at the same time as their clinic visit from getting any screening test at all.

The stakes are high, as the panel recommendation is poised to influence the ability of 50 million eligible adults to gain a new screening option. Scientific advancements can only benefit patients if they are able to access them, and the FDA now has the opportunity to help ensure this potentially life-saving test is available to all who need it.

With an FDA-approved blood test for colorectal cancer screening that is easily accessible for all people of average risk, we can improve screening rates, identify treatable cancers, and reduce the number of deaths from colorectal cancer. It’s time to enter a new era of options for colorectal cancer screening.

Access the full article on Real Clear Health…

Disclosures:

Dr. Samir Gupta is a professor of medicine at University of California San Diego within the Division of Gastroenterology and Department of Medicine. He is a consultant to companies which are developing colorectal cancer screening tests, including Guardant Health; InterVenn; Geneoscopy; CellMax Life; and Universal Diagnostics. He has received research support from companies which are studying colorectal cancer screening tests, including Freenome and Epigenomics.

Recommended Stories